When states start acting like businesses

The Trump Administration’s DOGE is a bull in the international relations China shop. It’s taken a wrecking ball to USAID, RFA, VOA, the Wilson Center and USIP - institutions of international relations that most of us grew up with and held to be inviolable. These institutions represented the best part of America - a narrative of peace, truth, justice, equality, democracy, and individual rights. Now, whether you believed it or not, that’s another story, but these and/or similar institutions were at the heart of this narrative and at the heart of the U.S. victory in the Cold War. Did anyone really think that the Wilson Center and USIP did anything but good?

Now, it’s no secret that governments around the world started to operate less like public institutions and more like corporations some time ago. From outsourcing essential services to adopting management jargon like “efficiency,” “performance,” and “customer service,” states have been reshaped by market logic.

Yet, arguably, one area that escaped this trend was diplomacy. Sure, ambassadors had to start better accounting for their time, embassies had to secure their KPIs, and employee travel compensation rates certainly went down(!), but relations between states remained pretty much insulated.

The corporatisation of government is now more than just a domestic policy change—it’s reshaping how states interact with each other.

Corporatised government is marked by several defining traits that reflect a shift in how power is exercised and how public life is managed.

First, there is a turn toward managerialism. Political leadership becomes less about vision or ideology and more about administration and public relations. Leaders take on the role of CEOs, evaluating their performance through short-term indicators—quarterly outcomes, media coverage, and the confidence of key stakeholders such as voters, donors, and credit-rating agencies.

Alongside this, the state increasingly relies on privatisation and outsourcing. Core functions that once defined the public sector—healthcare, infrastructure, even elements of diplomacy—are handed over to private companies. Public goods are no longer collectively owned or administered; they become contracts to be managed, priced, and delivered by the market.

Public policy itself is reframed through the lens of market metrics. Success is measured by GDP growth, favourable credit ratings, and cost-benefit analyses. Moral and social complexities are flattened into spreadsheet logic, where efficiency often trumps equity.

In this framework, citizens are no longer seen as participants in a democratic system, but as customers of government services. Civic engagement is reduced to a feedback loop of satisfaction surveys, where the pursuit of justice or the protection of rights is overshadowed by the goal of customer contentment.

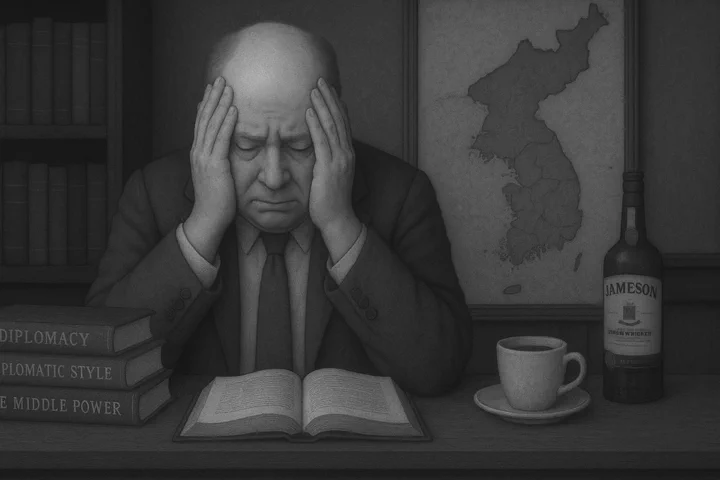

So what happens when two corporatised governments face each other on the world stage?

In a world increasingly shaped by corporatism, foreign policy begins to resemble corporate strategy. Nation-states act like brands, zealously guarding their market share. Alliances function more like joint ventures, forged not from shared values but mutual benefit. Humanitarian aid morphs into a form of public relations, while conflict is reframed as a kind of “risk management.”

The shift from principle to transactionalism becomes stark. Instead of values-based diplomacy, corporatised governments approach international relations with cold calculation. Concerns such as human rights, environmental sustainability, or long-term stability often take a back seat to short-term economic gains or strategic positioning. What matters now are deals, not diplomacy; leverage, not loyalty.

It could be argued that transactional diplomacy departs sharply from traditional diplomacy in both intent and method. While traditional diplomacy is grounded in long-term relationships, shared values, and the pursuit of mutual understanding, transactional diplomacy treats international relations as a series of isolated deals aimed at securing immediate benefits. Think real estate rather than diplomacy.

In this model, principles such as trust, loyalty, and multilateral cooperation are sidelined in favour of leverage, short-term gain, and zero-sum bargaining. Agreements are not built on enduring alliances or moral commitments, but on what can be extracted in the moment—whether in trade, security, or political support. The result is a more brittle, unpredictable international environment where stability is sacrificed for opportunism.

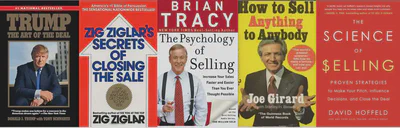

The qualities that define successful diplomats have shifted markedly over time, reflecting broader changes in the practice of diplomacy itself. Harold Nicolson, in his classic work on diplomacy, emphasized traits such as tact, restraint, integrity, and a deep understanding of history and foreign cultures. For Nicolson, the ideal diplomat was a careful listener, a patient negotiator, and a guardian of international stability.

By contrast, the ethos celebrated in The Art of the Deal values boldness, assertiveness, and the ability to dominate negotiations—qualities more aligned with salesmanship than statesmanship. The good salesperson, in this model, wins by creating urgency, leveraging pressure points, and prioritizing the close over the relationship.

As diplomacy becomes more transactional and media-driven, the traditional diplomat—measured, discreet, and collaborative—has increasingly given way to figures who resemble corporate dealmakers: charismatic, combative, and focused on the optics of success rather than its substance.

When two corporatised governments face each other on the world stage, strategic ambiguity becomes the norm. Like corporations hedging risks and masking intentions to secure competitive advantage, states adopt vague, flexible postures. Trade agreements are left intentionally unclear, support for conflicts is kept at arm’s length, and dual-track foreign policies are tailored to suit both domestic and international audiences. Clarity is no longer a virtue—flexibility and deniability are.

At the same time, public interest is increasingly subordinated to branding and performance. Governments pour resources into shaping international image and the narcissistic tendencies of leaders, often caring more about appearances than outcomes. Theatrics dominate policy.

Meanwhile, multilateralism struggles to survive in this landscape. Institutions such as the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, or international climate accords depend on cooperation, compromise, and shared norms. But corporatised states, focused on return on investment and domestic optics, have little patience for the slow, consensus-driven processes of global governance. The messy, collective work of multilateralism is difficult to package—and even harder to sell.

In this landscape, powerful states with strong “brands” and economic leverage dominate. Smaller or poorer nations are treated like junior partners in a global supply chain: expected to align, comply, or compete.

Crucially, the global public loses. When states become businesses, the world becomes a market. Inequality widens. Conflicts fester. Climate inaction persists. And diplomatic creativity—the ability to imagine new forms of global cooperation—atrophies. Essentially, there is no moral impetus.

Many academics have seen this same behavior in universities over the last two decades as corporatisation took hold. Longstanding departments and majors eviscerated, tenured positions replaced by adjunct lecturers, and times allotted to every action during the day. Soon after, research suffered as funds went towards projects which were more likely to bring about a return on investment (patents, joint-ventures, external funding, publicity) rather than simply expanding understanding and knowledge.

There’s a lot of similarities between the corporatisation of universities and the corporatisation of governments - given that they are both areas of society that just shouldn’t be corporatised!!!

Many academics will tell you that corporatisation wrecked academia - what’s coming for diplomacy?