Tariffs and an anti-American turn in South Korea

Anti-American sentiment in South Korea has always lingered just beneath the surface — a low hum that occasionally roars to life when diplomatic friction exposes the asymmetries in the alliance. Whether triggered by military accidents, trade imbalances, or perceived slights, the sense that Washington does not treat Seoul as an equal partner has long been a source of public frustration.

This week’s upcoming tariff negotiations risk stirring those feelings again.

South Korea’s Finance Minister Choi Sang-mok and Industry Minister Ahn Duk-geun will meet Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer for “two plus two” trade consultations - prompted by the imposition and subsequent suspension of “reciprocal” tariffs that impose 25 percent duties on South Korean products entering the U.S.

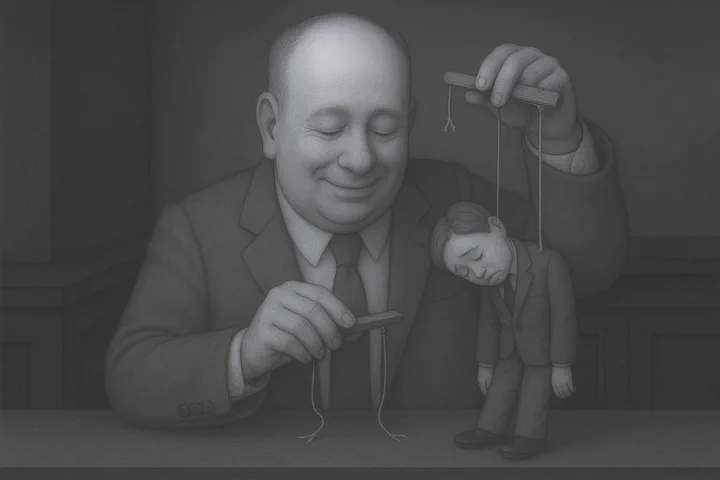

In diplomacy, where you meet matters. The venue chosen for the South Korea-U.S. talks — the U.S. Treasury Department — is not just a bureaucratic formality. It’s a symbolic demotion. Trade talks that affect the livelihoods of Korean steel workers, semiconductor engineers, and exporters are not being heard at the highest levels of the U.S. government. No Oval Office meeting. No direct involvement from the President. No White House Oval Office press moment.

Japan’s recent negotiations took place inside the White House, and even without the Prime Minister, Tokyo’s delegation was given symbolic prominence. President Trump participated and commented positively on the talks. Oval Office photos were taken, and the Japanese position highlighted. That contrast — highly visible, deeply felt — reinforces a perception in Korea that their contributions to the alliance are undervalued, and their concerns dismissed.

This will not go unnoticed in Seoul.

Worse than this, South Korea is entering the talks unprepared and poorly strategized. Even before the first handshake, South Korea appeared to agree to the U.S. desire to shift the focus of the talks.

Rather than limit the agenda to tariffs — a clear, transactional matter — Seoul pre-emptively agreed to expand the discussion to cover alliance dynamics, regional cooperation, and economic security. On arrival in Washington, Finance Minister Choi Sang-mok stated his aim was to make the South Korea-U.S. alliance “more robust.”

The intention may have been strategic: to remind Washington that the relationship is more than just steel quotas and semiconductor duties. But that framing comes with risks.

In the United States, especially under the Trump administration, nuance is a liability. A broad, values-based pitch opens the door for Washington to press unrelated demands: increased defense cost-sharing, alignment on China policy, or commitments in Indo-Pacific infrastructure. Worse, it dilutes the urgency of Korea’s core economic concerns — making it easier for the U.S. side to stall or sidestep tariff relief altogether.

Worse still, the Trump Administration needs a win as opposition mounts across all fronts. South Korea, as Trump’s “ATM” will be an easy ego-boost.

To the average South Korean, the optics are clear: their government is entering talks from a position of deference, tying sensitive economic issues to a wider strategic bargain — while their Japanese neighbors negotiate at the White House and get results.

Anti-American sentiment in South Korea is not new. It has flared at different moments throughout the history of the alliance — after military accidents, trade disputes, or perceived slights. Sometimes it is inflamed by the left, sometimes by nationalist conservatives. But always, it finds traction when ordinary Koreans feel their nation is being treated with disrespect.

In the early 2000s, it was the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) and a tragic armored vehicle incident that set off mass protests. In the late 2000s, it was an agreement to import American beef that brought thousands onto the streets. More recently, U.S. pressure on defense burden-sharing and strategic alignment with Japan has fed into public skepticism of Washington’s intentions.

The current tariff talks have the potential to tap into that same well of discontent. Not because of any single policy decision, but because of the cumulative sense of imbalance: that Korea gives more than it gets, that its economic pains are secondary to U.S. domestic calculations, and that its leaders must bend further just to be heard.

For the conservative hopefuls in the presidential election, the danger is real. Already facing a skeptical public at home, conservatives stake significant political capital on aligning closely with Washington. If these talks fail to yield tangible results — and worse, if they appear to lead only to more U.S. demands — the backlash will be swift.

Younger Koreans, already disillusioned by job insecurity, housing costs, and geopolitical instability, are increasingly questioning the benefits of an alliance that seems to demand sacrifices without offering economic stability. The optics of deference in Washington will not help. Nor will any agreement that appears to prioritize alliance politics over trade justice.

In this climate, even minor perceived humiliations, like being excluded from the White House, can snowball into political liabilities.

The alliance with the United States remains vital. But politics in Seoul are controlled by the pendulum swing of public opinion - and the Yoon Administration’s subservience to the U.S. pushed that pendulum to a height unparalleled since the authoritarian period.

As Finance Minister Choi Sang-mok indignantly crawls into Washington and offers everything that the U.S. wants and more, the perception of disrespect will deepen, and the costs won’t just be economic. They’ll be political, generational, and lasting.