South Korea’s epistemic capture

In South Korea, there’s an old leftist argument that the foreign policy of the country was long ago captured. It draws a straight line from the chinilpa - Koreans who collaborated with Japanese colonial rule - to the postwar conservative elites who aligned the country’s strategy with U.S. interests.

The claim is that foreign policy was never truly decolonized, merely transferred from one hegemon to another. The argument is largely discredited today… or is it?

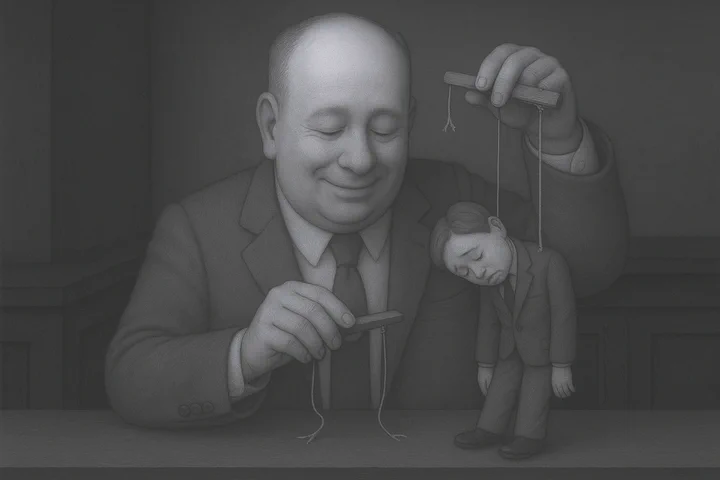

Recent debates have focused on the concept of “epistemic capture” - the slow, invisible takeover of a nation’s foreign policy imagination by U.S. paradigms, interests, and language that applies to many countries.

Epistemic capture suggests South Korea’s foreign policy isn’t a matter of alliance alignment. It isn’t a matter of shared interests. It isn’t a matter of mutual trust or values. It’s a matter of whose ideas define reality - and whose interests those ideas ultimately serve. There’s more than a skerrick of truth to the matter.

The vast majority of South Korea’s top foreign policy scholars and analysts are educated in the United States. They earn PhDs from American institutions, are trained in U.S. theoretical frameworks, and publish in U.S.-based journals where success is determined by fluency in concepts that reflect U.S. strategic priorities. Their careers, credibility, and institutional funding are often tied to how well they reproduce this intellectual ecosystem.

The end result, South Korean scholars learn not only how to speak the language of American IR theory - but how to think within it.

This dynamic may seem benign on the surface - an extension of academic globalization or alliance cooperation. But the consequences are far more serious. When the country’s intellectual class internalizes U.S. perspectives as objective truth, South Korea loses the ability to generate foreign policy rooted in its own national context. Decisions are no longer guided by Korean interests as Koreans understand them, but by what is legible, acceptable, and validated within the U.S.-dominated epistemic order.

The results are everywhere. Korean security policy is framed in terms of “extended deterrence” and “strategic clarity” - concepts crafted in Washington think tanks to serve American grand strategy. There is no better example than South Korea’s largest foreign policy issue - North Korea.

North Korea is rarely discussed in Seoul on its own terms, but as a threat to “regional stability,” a proxy for China’s ambitions, or a test of U.S. credibility. This is a direct consequence of epistemic capture: South Korean analysts, trained in U.S. institutions and judged by U.S. standards, reproduce interpretations that prioritize alliance optics over Korean agency - even when dealing with the issue most central to Korea’s own future.

China is similarly viewed primarily through the lens of U.S.-China rivalry, rather than Korea’s own fraught dependence and geographical proximity. And relations with Japan are squeezed into the Procrustean bed of trilateral cooperation, where any deviation from alignment is quickly labeled “emotional” or “anti-American.”

In this environment, alternative views - those that emphasize strategic autonomy, regional balancing, or Korea-first diplomacy - are routinely marginalized. Not because they lack merit, but because they lie outside the U.S.-approved vocabulary of legitimacy.

Academics and analysts who challenge these dominant narratives are often dismissed as ideological, unpatriotic, or simply unrealistic. Institutions that receive U.S. funding are rarely eager to support research that questions the alliance structure or suggests a more independent posture.

And young scholars? Seeing the professional risks, they self-censor accordingly - there’s no “next generation” program for independent thinkers but about seven of them for Korea-U.S. alliance scholars. It just makes sense to follow the rules. The circle closes before the conversation begins.

What makes this especially insidious is that the epistemic capture is often invisible to those caught in it. Because the frameworks are taught as “theories” and the vocabulary as “universal,” the U.S. perspective is mistaken for objective analysis. Korean scholars trained in the U.S. may believe they are being pragmatic or scientific, when in fact they are replicating foreign assumptions that obscure Korean realities.

A concept like “hedging” sounds neutral, but when applied uncritically to Korea’s position between China and the U.S., it may force false choices or obscure creative options. Similarly, the constant framing of Korea as a “linchpin” or “pivot” reduces national strategy to alliance maintenance.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was an attempt to “de-colonize” South Korea’s study of international relations and create a “Korea School of International Relations”. In the end, much of effort - including using terms and tropes such as “de-colonize” were simply replacing one ideological influence for another. The movement quietly disappeared.

Intellectual dependence has material consequences. It narrows Korea’s policy space, particularly when global dynamics shift. As the U.S.-China rivalry intensifies and domestic polarization deepens in the U.S., Korea faces a rapidly changing strategic environment. Yet its capacity to respond flexibly is compromised by the fact that its policymaking community is still working within a conceptual toolkit designed in - and for - Washington.

Rather than asking what is best for Korea under current conditions, decision-makers often ask what Korea should do to remain in good standing with the alliance.

Even more worryingly, this creates a feedback loop. Foreign analysts - especially those in the U.S. - observe Korean policy choices that echo their own language and frameworks and assume this confirms Korea’s alignment. But in reality, they are often hearing their own ideas reflected back through a Korea-based elite class trained to speak their language.

This presents a serious risk to alliance management - and that risk remains largely hidden.

When Korean foreign policy is articulated using the language and logic of U.S. strategic thought, it gives the illusion of alignment even when domestic priorities are shifting beneath the surface. What looks like consensus is often mimicry; what looks like convergence may be compliance.

To external observers - particularly in Washington - it creates a misleading sense of predictability. Analysts hear familiar words, see gestures that fit alliance expectations, and assume continuity. But the deeper undercurrents driving Korean decision-making - rising generational nationalism, regional recalculations, or public disillusionment with alliance dependency - often go unnoticed.

The result is a distorted mirror - one that shows harmony where there may be tension, and consensus where there is quiet dissent.

This disconnect raises the risk of strategic surprise. Outsiders believe they understand Korea because its policy discourse mimics their own. But when that mimicry masks a growing divergence, moments of rupture - such as unexpected outreach to China, shifts in North Korea policy, or sudden breaks with Japan - can seem abrupt or irrational. In reality, they are often the logical outcome of pressures long brewing inside Korea but misread or ignored abroad.

For allies, partners, and even rivals, this creates a dangerous blind spot. Understanding Korea requires more than listening for familiar signals - it requires recognizing when those signals are being performed, not believed. Without that awareness, the international community will continue to be surprised not because Korea is unpredictable, but because it has been consistently misread.