Koreans cautious about strategic flexibility

Washington under Biden, and now under Trump, are placing increased emphasis on “strategic flexibility” - the ability to deploy U.S. forces based in Korea to respond to regional or global contingencies.

Many Koreans are deeply uneasy about what this means for their country’s future. To them, strategic flexibility doesn’t just mean mobility. It means vulnerability.

Strategic flexibility raises the fear that the next great-power war might once again be fought on Korean soil.

At the heart of this concern is a deep historical awareness. Korea has repeatedly been the site of major conflicts between foreign powers - wars which Koreans neither started nor controlled, but which devastated their land and people more than any of the foreign actors involved.

The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), and the Korean War (1950–1953) were all launched by imperial powers vying for influence over Korea, but in each case, it was Koreans who bore the brunt of the destruction. This legacy of being used as a strategic chessboard continues to shape South Korean public opinion today.

In this context, strategic flexibility raises a fundamental question: Whose strategy is being served, and at whose expense?

While U.S. officials present flexibility as a means of deterring aggression and responding to threats across the Indo-Pacific — including crises involving China or Taiwan — many Koreans worry that this doctrine ties their country to any conflict the U.S. chooses to enter.

If American forces in Korea are mobilized to intervene in a regional war, would South Korea have a choice in the matter? Would it be seen as a co-belligerent by China? And more worryingly, would Korea become the first target in a retaliatory strike?

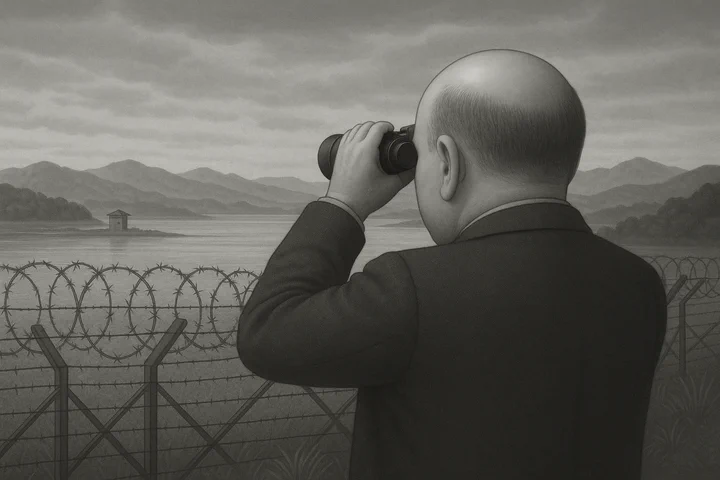

These are not hypothetical fears. Koreans are acutely aware of their geographic position — a peninsula neighbouring China, Russia, and North Korea, and within missile range of Beijing, Vladivostok, and Pyongyang. History points to the role of geography linking Korea to the region.

Taiwan and Korea were first linked at the start of the Cold War. In the late 1940s, China was ready to invade Taiwan. The confrontation in Korea, and China’s subsequent involvement, delayed and ultimately shelved Chinese plans. It’s absurd to think that any future conflict in Taiwan would not inherently involve action on the Korean Peninsula.

A conflict between the U.S. and China today would quickly draw the Korean Peninsula into the crossfire. U.S. military bases in places like Pyeongtaek or Osan would be seen as legitimate targets by America’s adversaries, regardless of South Korea’s formal stance in the conflict.

Unless there is a significant change in the Korea-U.S. alliance, Taiwan and Korea are linked. That is the dark promise of strategic flexibility: that American troops might launch a war from Korean soil, and it is Koreans who will suffer the consequences.

This concern is magnified by the ambiguity surrounding how much say Seoul has in such decisions. Although there was a bilateral understanding reached in 2006, clarifying that South Korea would not automatically be involved in all U.S. military operations launched from its territory, many analysts and citizens remain sceptical.

In the fog of war, legal agreements and diplomatic niceties often fall by the wayside. Once American troops in Korea are committed to a broader regional fight, South Korea will be drawn in — whether it likes it or not.

This isn’t simply a matter of national pride or political independence. It’s a matter of survival. South Korea is a densely populated, technologically advanced society with everything to lose in a major war. Think the before and after photos of Kherson or Gaza look bad? A conflict on the Korean Peninsula would make them look like the before and after of a Sunday school picnic.

While U.S. strategists may see Korea as a useful staging ground, Koreans increasingly wonder whether they are being asked to act as a buffer once again — a familiar role with a tragic history.

One of the most bitter lessons of the 20th century for many Koreans is that great powers do not fight on their own territory if they can avoid it. They fight on someone else’s land — and Korea has too often been that land. In this sense, strategic flexibility does not feel like a shield. It feels like a magnet, attracting conflict instead of deterring it.

That’s why the debate around strategic flexibility isn’t just a technical or military issue in South Korea. It’s an existential one. It touches on historical trauma, national identity, and fears of abandonment or entrapment.

Strategic flexibility will not be debated in the presidential election period - the conservatives can’t use it to politically wedge the progressives because it could potentially backfire, and the progressives in any case will play along as they have in every other election.

Yet, under the surface, dissatisfaction with the concept of strategic flexibility is growing. Sooner or later, that dissatisfaction will transform into policy action - and Trump’s “package deal” will likely hasten this.

It’s not that Koreans reject the alliance with the United States — far from it. They just want assurance that their country will not, once again, be treated as a battleground for others’ wars - and the U.S. cannot give this assurance.

Strategic flexibility remains a deeply contested concept — one that many Koreans view not as a promise of strength, but as a threat of repetition.