Foreign policy and neutral analysis online

Two pieces put out this week invited scorn. The first, “South Korea’s special envoys for… what exactly???”, used diplomatic tradition to criticize the sending of special envoys at the beginning of a presidential administration, invited praise from the right, and anger from the left. The second, “The challenges to Korean conservatism”, used American debates and local knowledge to criticize the ongoing failure to reform the conservative movement in Korea, invited praise from the left and anger from the right. I’m a born charmer.

With the scorn, it’s once again time to explain where I come from—to explain why I believe politically neutral analysis is difficult, but really, really important. Of course, I do realize, once burnt, there’s no amount of balm that can soothe social media butt hurt. So, there’s that.

Neutrality is routinely mistaken for indecision or weakness, but it is, in fact, something that requires discipline, commitment, and a certain disregard for social acceptance.

I’m very lucky that there are many who are very much part of even the extreme left and right in South Korea, who see the value in having an outside, politically neutral voice to better understand where the weaknesses in policy and/or policy communication sit.

So, I still get by. But it always helps to explain my position and hope that it makes clear why I believe analysts should strive to be as neutral as possible.

In the Australian government, I undertook analysis on national interest issues with a focus on North Asia; in consultancy, I’ve worked with leading geostrategy and human intelligence services providers, and multinational corporations; and in academia I slowly plod along seeking to find the truth to age old questions about middle powers and their role in regional global affairs.

In each role, neutral analysis has been essential. Each role rejects the notion that political identity should determine the value of an idea. It pays to look at each role individually.

Analysis. The aim of analysis is to inform decisionmakers, not to make policy. Analysts provide structured assessments based on incomplete and often ambiguous data, helping decisionmakers understand complex developments without prescribing what action to take.

The role of the analyst is not to advocate but to clarify by illuminating competing hypotheses, identifying assumptions, and defining the degrees of uncertainty. Analysis supports—but does not dictate—decision-making. The strength of analysis lies in its ability to communicate clearly the knowns, unknowns, and plausible interpretations of evolving situations.

To understand this fully, there’s no better place to start than the Psychology of Intelligence Analysis by Richards Heuer. Based on training manuals and best practice from the CIA’s Center for the Study of Intelligence (where you can download it if you dare) it consistently reiterates the importance of neutrality in analysis.

Heuer points out that the mind’s natural reliance on mental models, or “lenses,” means one must actively guard against cognitive biases (let alone social media infused biases). This is done through a conscious process of challenging assumptions, exploring alternative explanations, and applying structured analytic techniques like Analysis of Competing Hypotheses. Heuer stresses that mindsets form quickly and resist change, and thus the path to objectivity lies not in pretending to be bias-free, but in making reasoning processes explicit so they can be scrutinized and corrected.

Neutrality is not passive—it is the result of disciplined, self-aware thinking.

Critiquing left-leaning or right-leaning policies is not the same as taking sides. Neutral analysis is fundamentally about highlighting weaknesses, not reinforcing identities.

A critique of tariffs, for example, does not imply support for anti-Trump position, but rather an assessment how tariffs, as proposed and implemented, will not lead to the outcomes envisaged and communicated by the administration. Likewise, questioning progressive policies does not equate to endorsing conservative ones. Criticism, when rooted in analysis, is a hope for improvement rather than an act of partisanship.

Consultancy. Most audiences—whether individuals or corporate clients—do not seek truth. Readers often want affirmation of their existing beliefs, while companies frequently require analysis that satisfies compliance, corporate due diligence, or public relations needs. Reports that challenge assumptions are dismissed as “biased,” while those that confirm preconceptions are praised as “insightful.”

Like I said, I ain’t making friends or getting rich writing this crap (but do appreciate subscriptions and consultancies!)

The bias toward confirmation is not limited to corporate environments. Media platforms thrive on emotional reinforcement rather than balanced inquiry, and social networks amplify outrage rather than thoughtful assessment. As a result, independent analysis, which exists to question assumptions, is easily drowned out. The hostility directed at neutral or non-partisan analysts is consistent and predictable. It goes something like this:

- You got no friends! Without alignment to a political or ideological camp, neutral voices receive attacks from all sides. There is no built-in audience rushing to your defense—only a rotating cast of critics, depending on whose narrative you’ve just challenged.

- You’re a twat. Neutrality is misread as moral superiority or “fence-sitting.” Even when the intention is clarity, neutrality is often heard as sneering dismissal by those who view disagreement as disrespect.

- Your enemies grow. Criticizing both sides eventually alienates both. One critique from the left and one from the right may seem balanced to the analyst, but to partisans, it feels like equal betrayal.

- You’re dodgy. In polarized contexts, non-alignment is viewed as a mask for covert loyalty. Neutral positions provoke questions like “Who are you really working for?” because certainty is more comfortable than ambiguity. Trust me, I hate everyone.

- The algorithm hates you. Social media amplifies sensational and partisan content, burying nuanced perspectives. Neutral analysis lacks the emotional hooks—rage, identity, tribal pride—that drive virality and algorithmic favor. If you can find my work, you’re either lucky or unlucky, but that depends on your point of view.

- Gatekeepers ignore you. Partisan commentators and institutions dismiss independent work to maintain their dominance. They treat neutrality not as a stance, but as a threat—one that destabilizes their narratives and undermines their authority. For those with a team of panhandlers and sycophants re-posting their views, the views of an independent analyst ain’t worth commenting on or responding to. That’s pretty much okay with me.

As I’ve said, in the end, I’m not doing this to get likes, retweets, or consulting gigs from boardrooms looking for mirror reflections. Independent analysis may be provocative, discomforting, or lead to silence, dismissal, or even attacks, but one thing is sure: I ain’t lying to myself, or to others. That, at least, is worth something—even if it doesn’t trend.

Academia. Then there’s academia… oh academia… International relations academics have a responsibility to contribute to public debate, offering clarity and context in a world increasingly shaped by confusion and conflict. But for many, it’s hard to maintain neutrality.

Many academics online operate like horses with blinders—fast and focused but incapable of seeing the wider field. Their values shape not just what they believe but also what they refuse to consider. The temptation for academics in certain circumstances to wear blinders is strong. I’ll give two examples:

- If you’re a Korean IR academic, it makes sense to choose a side. Positioning yourself behind one party or the other opens doors to academic advancement, government boards and task forces, positions in the foreign ministry, or even ambassadorships. In contrast, as a foreign academic in Korea, those rewards are absent and pushing too hard on one side or the other risks inviting scorn and even visa issues.

- If you’re a scholar of Korea outside the country, it makes sense to see everything Korea does as perfection multiplied—no matter what. This way, you receive plenty of Korean government funding, invitations to conferences, and if you’re real smarmy, you may even receive the endowed chair award of permanent funding and sycophancy. In contrast, as a foreign academic in Korea, there’s nothing doing. According to a colleague in government, the general perception is that non-Korean foreign policy academics in Korea aren’t very important(!) and/or are already self-censoring so they’re not much of a reputational risk—they can be ignored.

So for me, it makes perfect sense to just keep on plodding along and criticize what needs to be criticized, and keep shtum on the really controversial issues.

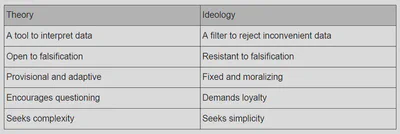

It’s still weird for me that many academics online forget the differences between the theory that they push in their academic research and the ideology they push online. The difference between theory and ideology is stark:

Theory is a framework for exploration, while ideology is a barricade against it. Where theory invites questions, ideology demands allegiance—and shuts the door behind it. Even in media interviews and on social media, academics should hold themselves to higher standards. Sure, it doesn’t make for a great media interview or a viral social media post, but those standards are important.

In the end, I don’t give f@ck

In an age dominated by political and ideological loyalty tests, taking a neutral line is getting harder and harder. I still believe society needs neutrality to remind us that facts and outcomes should still guide decision-making.

This is true (and essential) in government, consultancy, and academia. As a testament to my belief, it’s pretty clear that I’m not here to make money or jump up the academic ladder. If I were, I’d be shilling for one side or the other, building up the numbers, and confirming every vanguard viewpoint the algorithm spins my way. I’m not doing this.

I’m not shilling because I don’t really give a f@ck. I’m an old, grumpy, anti-social academic who hates everyone equally (those who know me offline are aware I exaggerate this point somewhat online).

You reach a point in life where experiences let you know that time is limited and conforming to crowd expectations or fitting in is less important. I’ll probably sooner or later disappear from this space either physically or mentally—if somebody wants to pay me big cookies (everyone has a price), but until then, no punches will be pulled.

Ultimately, what matters is not which side wins an argument, but whether the resulting policy is effective—whether it works. Both the left and right produce examples of thoughtful, well-crafted solutions as well as flawed, performative, or harmful policies. Just like intelligence successes don’t attract headlines, policy successes rarely attract attention. It is easier to criticize than to commend, but that’s how we learn.

The strength of independent analysis lies in its refusal to accept the comfort of belonging to a camp. Groucho Marx’s line captures this sentiment: “I’d never belong to a party that accepted me as a member.” Neutral analysis is not about belonging—it is about seeking clarity, regardless of whose narrative it disrupts.