Another Trump-Kim summit? Please no!

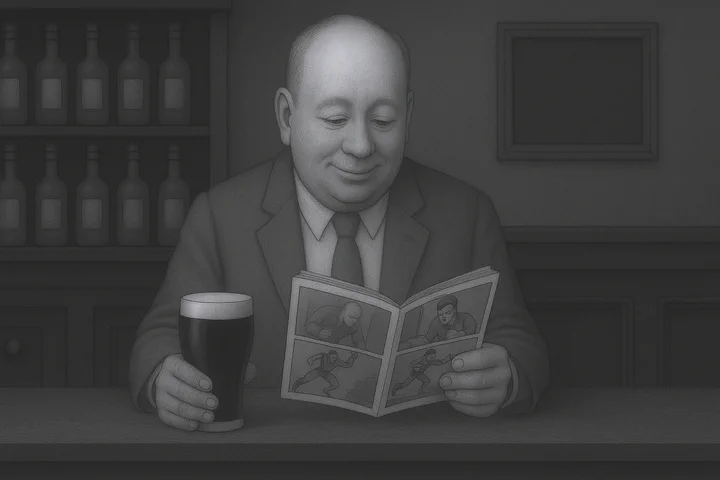

A long time ago, in a university far, far away, I spent late evenings reading dusty and dated international relations texts. In some of those texts, there were pencilled messages passed between students over decades, Things like: “The CIA stuck pages 27 and 28 together”; and “This text helped me. There’s no toilet paper on Chifley L3” or “The professor who assigned this text never read it”.

Looking through similar dusty and dated international relations texts here in Seoul, I’ve not seen a single pencilled message marking the passage of time. Maybe here lies the failure in South Korea’s foreign policy - no creativity?

This week there was hope for a meeting between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un at the bookends of APEC during 31 October to 1 November. You gotta wonder though. Did anyone really think there’d be any purpose? Is this the limit of imagination in South Korea’s foreign policy? Really, we need more pencilled messages in South Korea’s foreign policy! Let me explain…

First, the Korean Peninsula is an incredibly stale and fetid diplomatic sore that will not be solved by yet another summit. For a quarter of a century, South Korea has poured immense energy into staging high-profile summits with North Korea, each heralded as a “breakthrough” and framed as the dawn of a new era on the peninsula. Yet the results are painfully clear: nothing fundamental has changed. North Korea remains a nuclear-armed state, inter-Korean economic projects have withered, and hostility continues to flare across the DMZ.

These summits, with their photo ops and carefully scripted declarations, serve more as theatre than diplomacy. They substitute spectacle for substance, allowing leaders to claim statesmanship without addressing the structural realities that keep the two Koreas apart. The parade of summits since 2000 demonstrates the futility of expecting creativity or lasting progress from rituals designed primarily to recycle old promises under fresh headlines.

The only summit that carried genuine purpose was the first one in June 2000. It was the culmination of Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy, a genuinely new and innovative idea that broke with decades of sterile deterrence and hostility. It was an idea - a new idea.

For the first time, a South Korean leader openly and successfully argued that engagement, rather than containment, might transform the peninsula’s dynamics. The summit was not simply a meeting—it was the symbolic anchor of a strategy that reimagined inter-Korean relations, marrying humanitarian outreach with economic cooperation.

Every summit that followed became a pale imitation. Instead of launching new frameworks or bold departures, they recycled the same tired formulas of joint declarations, family reunions, and vague commitments to peace. Without the originality and daring that underpinned the first encounter, subsequent summits devolved into ritualistic pageantry: photo opportunities without policy substance, a carousel of handshakes that neither reduced nuclear tensions nor shifted the structural balance of hostility.

In hindsight, the 2000 summit stands out not because it solved anything, but because it at least embodied an innovative, fresh strategic concept—something absent from the hollow theatre that followed.

Second, Trump is just about the last person on earth who a sane person would turn to in order to secure progress on solving problems on the Korean Peninsula. His summits with Kim Jong-un were not rooted in strategy, but in pure travelling snake oil salesman showmanship—staged for television ratings and domestic political points rather than substantive policy outcomes.

The Singapore and Hanoi meetings generated plenty of headlines and historic photographs, yet they left the nuclear issue as unresolved as ever, while giving Pyongyang an unprecedented degree of international legitimacy at no real cost. Unlike the 2000 summit, which grew from a carefully considered policy shift, Trump’s meetings had no underlying framework or follow-through, ensuring their collapse into empty spectacle. AND on top of it all, he started the whole f*ckup with his fire ‘n’ fury. He half-solved a problem he himself started.

Third, even if you did decide to turn to Trump for help, he’s busy - and will be until he needs a solid distraction. Trump will be swamped with Ukraine and Russia; killing tuna fishermen off the coast of Venezuela; supporting Israeli genocide in Gaza; and likely, by the end of the year, bombing Iran—leaving no real bandwidth for Korea.

The only time he’ll bother is if it offers a quick shakedown for cash or a flashy distraction from his other failures. Any talk of peace or denuclearisation will be window dressing. For Trump, Korea is just another stage prop in the endless grift.

The lesson is simple. Without “fire and fury,” the Korean Peninsula fades into the background. Trump thrives on crises that demand bold declarations and theatrical gestures. Korea today offers none of that. The region is stable enough to be ignored, yet volatile enough to remain unsolved.

If a meeting occurs after APEC, it will be a spectacle without consequence—a hollow echo of past theatrics. Jean Baudrillard will be rolling in his grave as we have another copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of real diplomacy. To imagine otherwise is to misunderstand the brutal arithmetic of Trump’s attention. Korea will only matter again when the Peninsula itself generates crisis, noise, and danger. Until then, the world should not expect serious attention from Washington.

The conclusion practically writes itself. South Korea cannot keep waiting for outsiders to solve its problems, because outsiders are either indifferent, incompetent, or opportunistic. The endless parade of summits shows that the United States cannot deliver, and that North Korea will not change because of handshakes and photo ops.

Creativity, the very thing missing from the pencilled margins of Seoul’s diplomatic texts, is the only way forward. New approaches must be crafted at home, not imported from abroad or staged for cameras in Singapore hotel lobbies. What Korea needs is not another recycled summit, but the courage to scribble new ideas into the blank margins of its foreign policy—to risk embarrassment, to try what has not been tried, to look past Washington and Pyongyang and sketch its own solutions. Only then can it escape the stale cycle of spectacle and disappointment.

When I was last home, I went back to the same library shelves and read through the pencilled notes. Students were still creatively updating conversations that started in the 1960s. Without such pencilled notes, South Korea’s diplomacy will remain as lifeless as the textbooks in its libraries—carefully preserved, but no capacity to read between or imagine a world beyond the lines.